Triangles of velocities? Forget them. They got you through your navigation exam, but your GPS is what you’ll use to keep on track. Now you have to learn how to actually plan for a trip to another airfield. So, what do you in the real world?

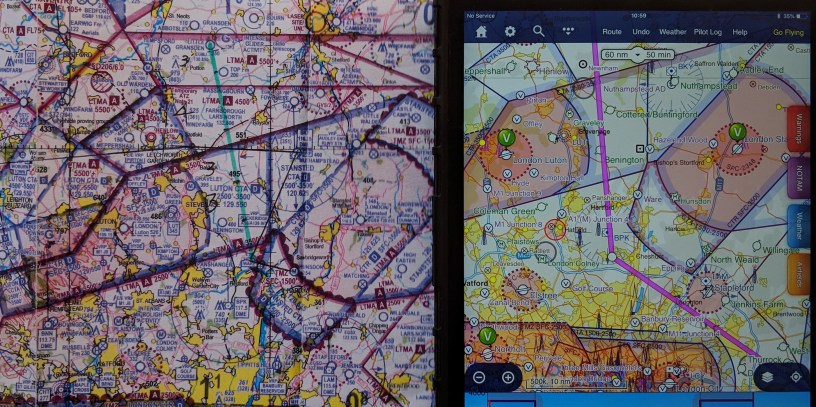

Drawing a straight line from A to B is a good start. Then you take a good look at where that takes you. Can you fly there, or are you in restricted airspace? Don’t immediately assume you can’t fly through an area – there are usually levels of flight allowed. Perhaps you need to remain under 1500 feet here or go over 3000 feet. Down in the South it is almost impossible to avoid the big red blocks of Heathrow, Stansted, Luton, Gatwick and Southend. The London TMA keeps you under 2500 feet across a huge swathe of the South, danger areas abound, and in summer, there seem to be hundreds of air displays that block your route. Often, skirting a TMZ or CTA can add only a couple of minutes to your route and save you masses of stress on the radio.

“Flying is as easy or as complicated as you make it,” says the CFI. Choose somewhere that’s popular with others at your club, where you can pick your fellow pilots’ brains for local knowledge that will make your trip simpler. If you don’t need to talk to anyone else on the radio, don’t.

Look up your destination airfield and its runways, try and find out which is the preferred runway when all else is equal. It’s usually the one that is uphill, longer or offers an easier approach, but of course the wind may dictate otherwise. Studying the route on Google Earth will help you familiarise yourself with the area. Try and find markers that are significant visual reporting points. Ted Barrett, still flying at 97, never uses a map in the local area. “I use rivers, roads and railways when I’m flying,” he says. It is easy to get used to certain agricultural landmarks, and then find yourself lost when they disappear – the bright yellow rape seed field turns green or the quarry no longer stands out against the brown surrounds. Realising that you will be flying with a dam or a reservoir on your left, or a power station on your right will help you keep on track, even if they are far away. Do a mental run-though of your route as you look at the map – are there towns or woods, both of which will give you more air turbulence. Read everything you can get from the airfield’s website, which is sometimes woefully little. You may find more information on a Pooley’s or Skydemon plate.

On the day print out a pilot’s log, or plog, from your navigation software, to give you current wind and compass directions. Check the Notams to see nothing is happening that should interfere with your trip – a flypast of the Red Arrows, for example. Phone for PPR if needed – and it usually is – and ask which runway is currently in use, even though that could change en route, circuit height and joining procedures. Write down the radio frequencies you will need, and those you may need as an alternative, should anything go wrong. Make sure your electronic equipment is fully charged, and you have some sort of backup should you need it. I have a Skydemon on a tablet, and on my phone and most pilots I have flown with have at least two options for GPS.

As you fly, do frequent sanity checks to make sure you are heading in the right direction. I have heard old hands talk about getting lost in their local area until they found a significant marker to help them back on track. Mark your route on a map with a non-permanent marker, with enough points to keep you on track, and not so many you have your nose in the map.

Then, with all your checks done, take a deep breath, line up on the runway, think how lucky you are, and open the throttle!

Thanks Nushin, good stuff.

One are you didn’t touch on was time and fuel. That was probably the main useful output of the triangle of velocities – and if not using that then you need a software version to output the same info. Work out how much fuel you will need for the trip and carry as much reserve as you can.

With a microlight the payload may be quite limited on what you can legally carry and you need to make some educated choices if you want to avoid flying illegally then some fine calculations may be needed or an interim stop.

With the nights drawing in fast the time element can be a big consideration too – I have seen many people caught out over the years as summer slips away towards Autumn..

So abandon the manual triangle of velocities if you please – but make sure you use planning software to replace it and think and act on the information it gives you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Paul. You are right, I didn’t say anything about that. I suppose at my stage, going for even an hour is quite a big deal, and if you leave with full tanks, you won’t have a problem. It is certainly something to think about though for long distances. My B is just a lot closer than yours would be!

LikeLike

2 people = only a little over an hours fuel in a lot of machines to be legal – so that B doesn’t have to be far away at all …;)

Roll on that weight limit change …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, in my trusty Skyranger, I can do more than that and still be legal!

LikeLike